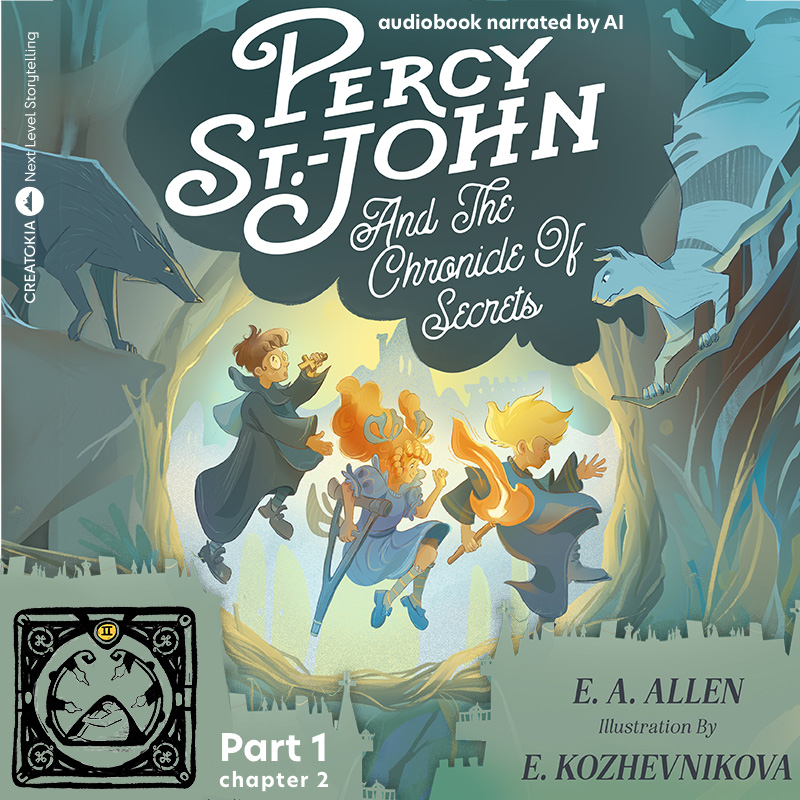

Discover the Mystical World of Percy St.-John and the Chronicle of Secrets

listen and read along - Part 1 - Chapter 2

Glossary | Press | audio books | About the Author | overview

chapter 2

Wherein Percy is Accused

Chapter 2

1

Just then the great bell began to ring, almost shaking us off our feet. Percy glanced at me wide-eyed. “Vespers (4.30 p.m.), and we’ll be late again for sure!” he shouted, covering his ears with his hands.

I couldn’t hear him above the noise of the bell, but there was no need to tell me what to do. We dashed for the hatch and slid down the ladder at a speed only a little short of a free fall. I went first and I remembered thinking that if I stopped Percy would surely crash into me and knock me loose.

Once at the foot of the tower, we scurried across the church and into the chapel, where the monks had gathered ahead of us. Once again Percy and I brought up the rear, under the disapproving eyes of the older monks. We sat without looking up.

There was already a special excitement in the air. It was the Day of Ashes* and the entire monastery was entering into the joy of anticipating the day of Our Lord’s Resurrection. Father Abbot arrived a little late — more’s the relief to Percy and me — and as he took his seat, Prior Oswald entered, looking around, his eyes wide, and it seemed to me, distressed.

The Prior is a tall, bulky man with a long nose, small mouth, and large ears. He has a way of towering over others and looking down his nose in the most unpleasant way. I hesitate to say it, but it has always seemed to me that Prior Oswald is excessively proud of his place as second only to Father Abbot in the leadership of our community, and he makes no secret that he hopes God will place the Abbot’s cross upon him someday.

Oswald rushed to Abbot Bartholomew’s side and began to whisper excitedly in his ear. Father’s Abbot’s face grew white, and his eyes bulged.

Father Abbot’s expression grew more pained the longer Prior Oswald whispered. When the Prior had finished Father Abbot motioned him to take his place, and from that time on we chanted* our prayers. When we’d finished and prepared to return to our work, Abbot Bartholomew stood. “Brothers,” he said, grim-faced, “a terrible thing has happened. One of the books of our Scholarium is missing. Sadly, the missing book is the rarest and most treasured of our collection, because we know it once belonged to our dear Saint Hilda.”

The brothers gasped and fell to puzzled murmuring, but none spoke. The Abbot, his face long, pale, and grim, said no more but dismissed us to our duties with a wave of his hand.

2

Later, after supper, Prior Oswald came to the table where Percy sat, and I heard him say, in a stern voice — Prior Oswald’s voice always reminds me of curdled milk — “The Abbot wishes to see you, Brother Percy.” It’s an odd thing to be summoned by the Abbot at that time of day, and because of all the commotion earlier, I was sure all the brothers wondered, as I did, whatever was afoot.

Percy told me later that he had to get up his courage as he approached the Abbot’s study — a small, bare room adjacent to a bedchamber. He knocked gently at the door and heard from inside the stern command, “Come in.”

“You wished to see me, Father Abbot?” Percy asked, his eyes darting from corner to corner of the room.

Abbot Bartholomew — a tall, slender man, with a long, angular face and a bald dome of a head — stood as Percy entered, his hands tucked in the sleeves of his black robe. His small mouth puckered, and his cold blue eyes seemed to pin Percy’s feet to the floor.

“Please sit,” he said, frowning and motioning with a sweep of his hand to a chair near the crackling hearth. When Percy had taken the chair, the Abbot continued to stand. “I have summoned you, Brother Percy, because of the missing book.”

“Yes, Father Abbot?” Percy asked.

“Prior Oswald tells me you’ve often used the Scholarium and have customarily studied in the same room where the book was kept.”

“I have often used the Scholarium, Father Abbot. I read both Greek and Latin, you see, and I’ve been making some notes on — ”

“Yes, yes — well... that’s all well and good,” the Abbot cut him short. “But it’s the missing book that concerns me just now.”

“Yes, sir?” Percy blinked and swallowed, not liking the way the conversation was going.

“Oswald testifies that you were the last person to leave the Scholarium last evening, just before Compline (6 p.m.). He had some work to do elsewhere, so he asked you to lock up and to return the key to him as we gathered to pray.”

“Yes, that is so,” said Percy.

“I will be plainspoken with you, Percy St.-John,” said the Abbot, now frowning and his voice cold. “Given what I know of your past and the troubles you’ve caused before coming here, I must suspect that you are the thief. I give you fair warning. You’ll not be able to take the book you’ve stolen from the monastery, so you best return it to me now. I’ll make no further fuss about the matter, though I will, of course, inform your French employers and tell them you are to be expelled from the abbey.”

“But Father Abbot,” Percy protested, rising from his chair, “I have not taken the book! I’m innocent! I don’t even know what book is missing!”

“Come, come, boy. You needn’t play the innocent with me. It must be you who took our book, and I tell you now I mean to have it from you,” he said, stiffening his neck and crossing his arms, as his eyes narrowed.

There was a long silence. Percy’s mouth suddenly ran dry with fear.

“Very well, Brother Percy,” the Abbot continued. “I’ll not confine you just now, because we have yet to make a thorough search of your things. The book could not have been taken from the monastery, because no one has come or gone since it went missing. We will find it where you’ve hidden it — you may be sure of that — so at least we will have the book and the proof of your guilt. Now go. Continue your duties, but be warned,” he said, his eyes cold. “I know what you’ve done.”

Percy stood and left the Abbot’s study, without another word in his own defense. He could see Father Abbot had already declared him guilty and would listen to none of his claims otherwise. “Convicted without a trial,” Percy told me later, “and nothing I could do about it.”

In the narrow passage just outside, Percy found Prior Oswald, looking down his nose with a scowling face. Brother Oswald never smiles and always speaks of discipline and penance. He is also one of those who speak often of God’s wrath.

“Return that book, Brother Percy,” he said menacingly. “Repent your sin,” he added and continued to glare, as Percy made his way down the passage. From Prior Oswald’s attitude, Percy knew that few would believe him and he could only escape the accusation by finding and returning the book himself. At least, that’s what he had decided by the time he descended the night stairs and once again drew a deep breath in the crisp air of the Cloister.

While Percy was with the Abbot, I found myself thinking how frightening it had been to see Percy in a trance and then the old man who looked like an angry God. Now, I dared not tell anyone what I’d seen on the tower, lest they should declare Percy possessed by Satan. I also still feared they might think me insane. As I walked along the dark passage to my cell in the Dorter, with those thoughts dancing in my head, I heard a low growl — like the snarl of a wolf.

I stopped to look behind me, and it was then I heard it for the first time — the faint sound of a chorus*, chanting an evil-sounding hymn. It grew louder and louder as I hurried to my cell, but when I threw myself on my cot and covered my head with my pillow, it stopped.

3

The horror of his meeting with Father Abbot and then Prior Oswald left Percy feeling as if he’d just escaped from a monster. The words “Return that book!” echoed in his mind all night and even as he came into the Refectory the next morning for breakfast. His face looked to me even more dismal, and I saw too that the other monks were casting secret glances at him, just as they had done earlier, at Lauds (5:00-6:00 a.m.). The thick fog of suspicion had fallen over Brother Percy, and there was no defending against it. Prior Oswald had spread the news of Percy’s “crime” among the brothers. I could not remember such whispering and disturbance in the abbey — not since three years earlier when old Brother Valerian, the gatekeeper, had confronted a snarling demon, roaming about the forecourt in the small hours of a December morning. At the time, I had doubted Brother Valerian’s story, but now I was not so sure.

When Percy took his place at a table, none of the other monks took a seat beside him, or even near his place. I decided to show my disdain for their behaviour. I moved immediately to sit directly across from Brother Percy. I smiled at him too, so everyone could see.

When the Abbot and Prior had arrived and were seated, the brothers who serve meals came with our bowls and cups, and the brother charged with reading the Scripture at that meal commenced his reading. There is no talking permitted at mealtime, except by the reader, and so afterward I followed Percy to the nearby Locutory, where speaking is permitted at some times of the day.

“Brother Percy, the monks are saying the Abbot summoned you because you surely took the missing book. When I passed your cell earlier Prior Oswald and Brother Jean-Baptiste were in there — searching it,” I whispered.

“Yes, I figured everyone would know by now. Well, I have nothing to do with the missing book. No one has even bothered to tell me what book I am supposed to have stolen. What is this book, exactly? I’ve never heard of it.”

“That’s because you were not permitted to know of it. Only those who have been a monk for ten years are permitted to know of it, and only the most senior monks are permitted to see it.”

“What is it? What’s it called?”

“It has no name that I ever knew, and so the monks call it merely the Cronica mysteria.”

“The Chronicle of Secrets? What’s it about?”

“I don’t know. Never seen it myself... at least not that I know. I might have dusted it when I’ve cleaned the Scholarium. Oh no... maybe I wasn’t permitted even to tell you the name of the thing.”

“Listen, Gabriel,” said Percy, taking my forearm. “You seem to want to help me, and I’m dashed grateful for that, but if you wish to help, you mustn’t hold back. I can’t get myself out of this mess if I don’t know everything about the crime I’m accused of committing. I must find that book... to clear my good name.”

“But you don’t have a good name, Percy. In fact, your name is — ”

“Yes, well, putting all that aside, I’ve got to have that book to stay out of prison.”

When Percy said the word prison, a look came in his eyes that I’d not seen before. Percy was frightened.

“Yes, I guess you’re right there. And I do wish to help because I do not believe you are guilty, Brother Percy. Even though you are a troubled soul because of your past thievery. Still....”

“Let’s have it, Gabriel. No holding back,” he insisted, frowning. “What do the monks say about that book?”

“The book is a manuscript of the twelfth century, in the time of our beloved Saint Hilda, as Father Abbot said. It’s said to have been brought here, from Ireland, by Saint Hilda herself. That’s why it’s so revered. It was the property of our saint.” I crossed myself.

“I see. What’s this book, precisely then? What does it say?”

“I have no idea. No one has ever told me.”

“But, what do the brother monks say it’s about?”

“It’s in the title. It is said to convey secret knowledge. Frightening secrets, Percy. Only one as saintly as our dear Hilda would dare to read it, they say.”

“What frightful secrets?”

“I don’t know. Just secrets, I guess. Frightful secrets, they say, and that’s enough to keep me away from the thing. If I ever come face-to-face with it, I will surely close my eyes and pray.” I crossed myself again.

Percy frowned and shot me a disappointed glance. He fell silent, too. It was a thick kind of silence, like the gruel that’s served in our Refectory. Then he said, “Very well... but one thing is clear now.”

“What?” I asked, thinking that almost nothing was clear to me.

“If I don’t find that book, I’m in serious trouble. Big trouble. A peaceful year in this abbey was my last chance. If I don’t clear myself, the people who sent me here — the French mainly — will lock me away somewhere and forget about me.” Then he repeated, mainly to himself — “and forget about me.”

That left me to wonder why exactly Percy had been sent to our monastery, and who were those French people he was talking about?

Glossary | Press | audio books | About the Author | overview